What role did the katana play in samurai culture beyond its use as a sword?

The katana in samurai culture was far more than a sword - it was the physical embodiment of a samurai's identity, social status, and moral commitment. The concept of the sword as the soul of the samurai, tamashii, expressed in Japanese as 'bushi no tamashii', was not metaphorical but a practical philosophical position that shaped how samurai understood their relationship to their swords. A samurai was responsible for the care and condition of his sword in the same way he was responsible for his own moral condition - a neglected sword indicated a neglected character. The two swords of the daisho pairing were the exclusive privilege of the samurai class and were required to be worn whenever a samurai was outside his home. They were not simply weapons but markers of identity that could not be separated from the person who carried them. When the Meiji government banned the wearing of swords in 1876, ending centuries of samurai sword culture, the psychological and social impact on the samurai class was profound - the prohibition removed the physical marker of their identity in a single regulatory action.

What makes a samurai katana different from a general katana in this context?

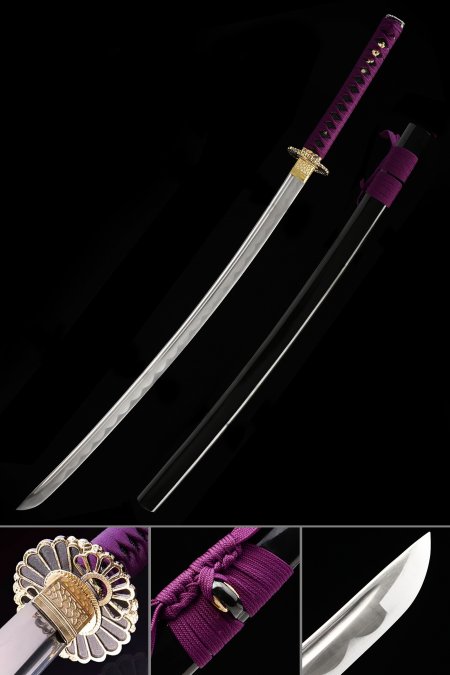

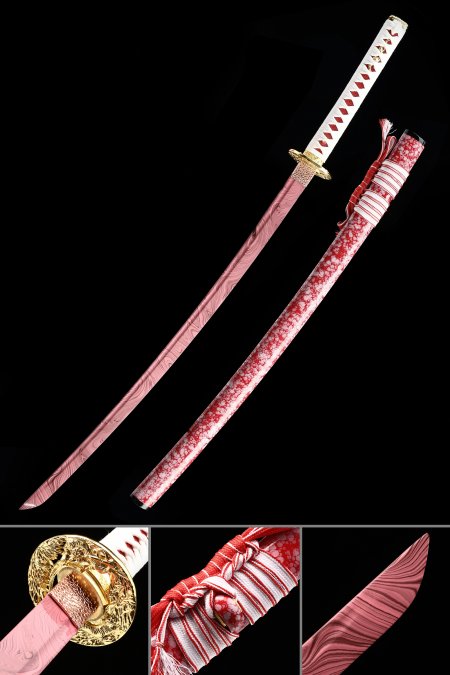

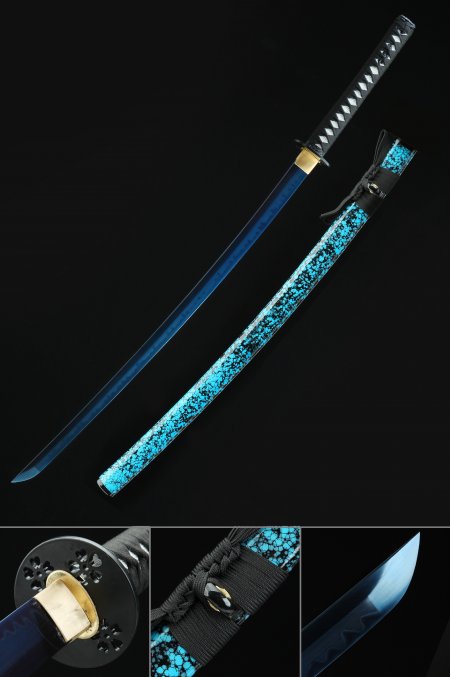

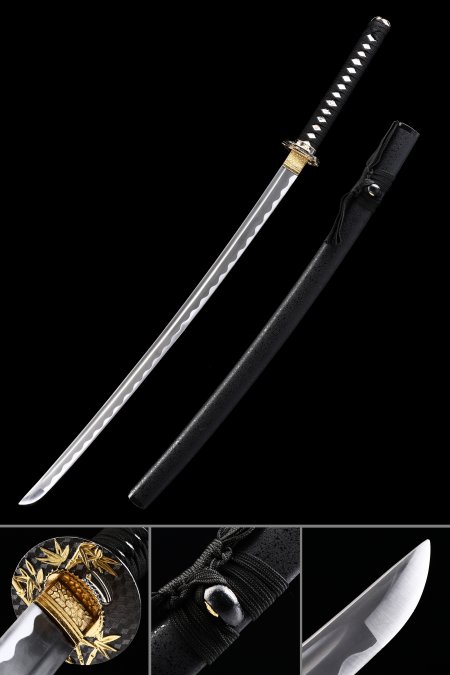

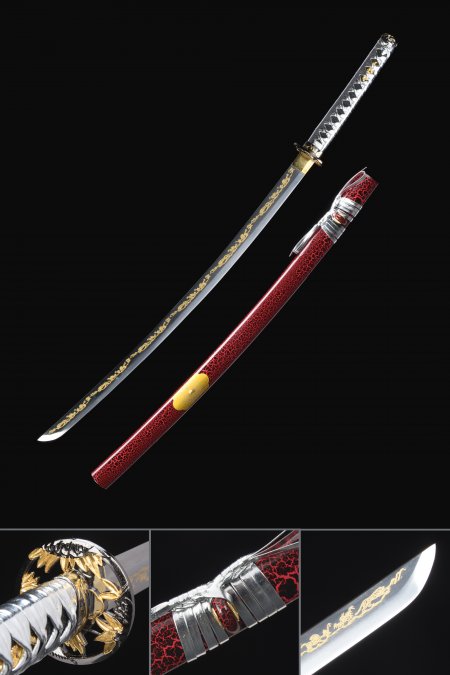

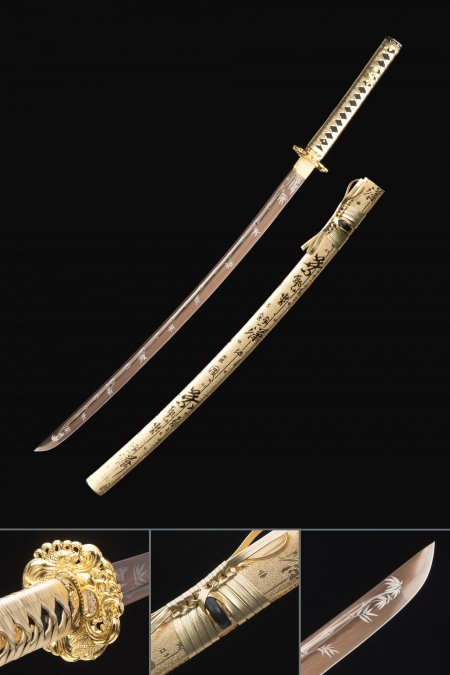

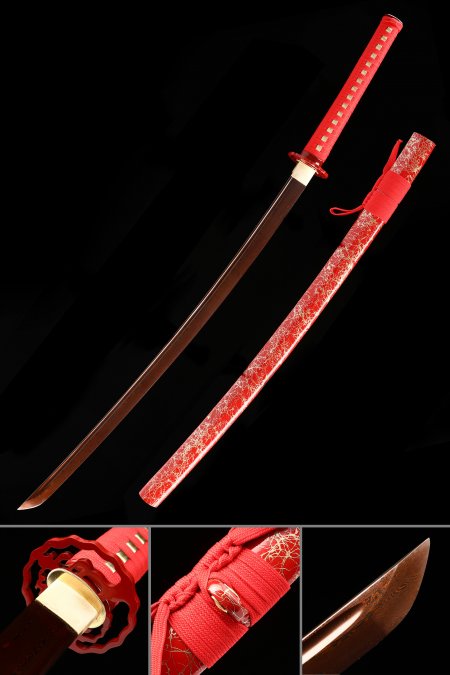

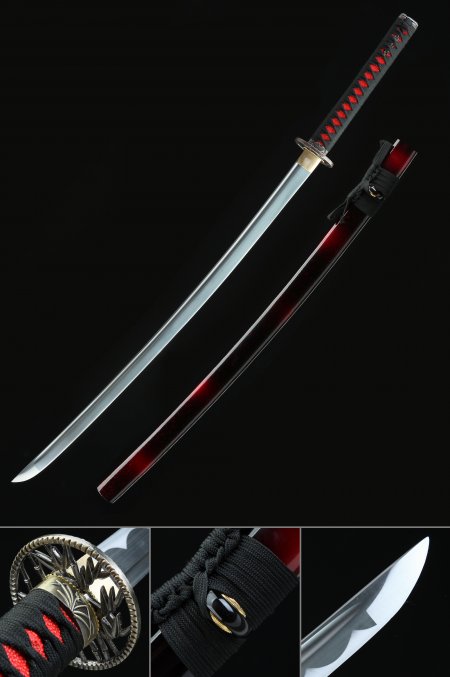

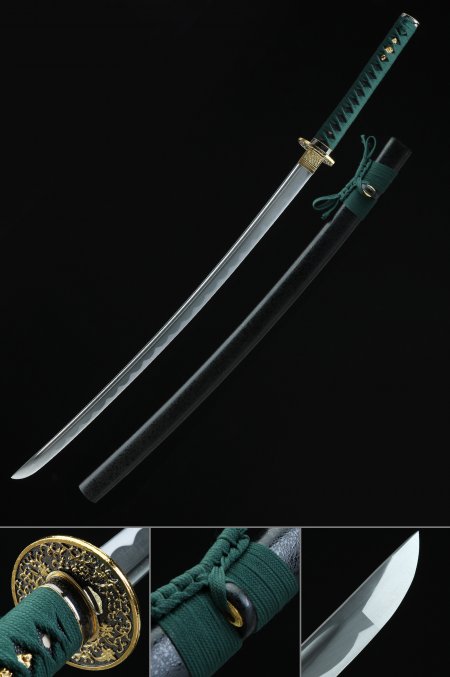

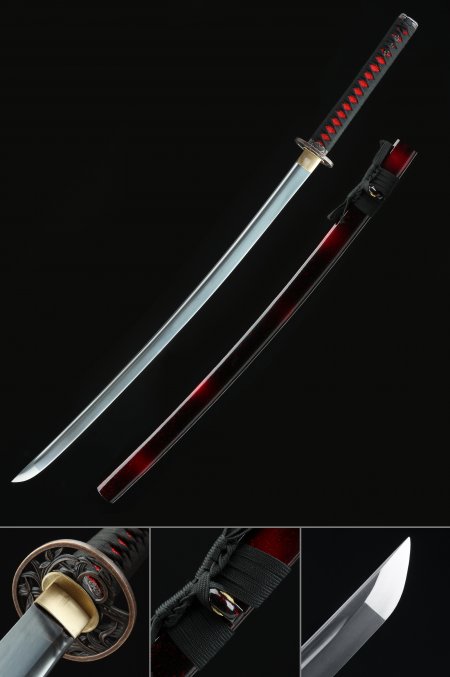

In this collection, samurai katana and katana refer to the same category of hand-forged Japanese swords - the term samurai katana emphasizes the historical and cultural context of the sword's tradition rather than indicating a different type of sword. All katana in this catalog are built to the same construction standards: high-carbon steel, full-tang construction, traditionally fitted components. The samurai katana framing positions these swords in their historical context - as objects that exist in direct relationship to the centuries of Japanese martial and cultural tradition associated with the samurai class. For collectors, this framing is relevant because it reflects why these swords matter as collected objects: not just as well-made steel artifacts but as physical representatives of one of the most developed and historically significant martial traditions in human history. The construction standards are identical to those in the real katana, full-tang katana, and handmade katana collections - the difference is in how the collection positions the swords' cultural significance.

How has the samurai katana evolved from historical examples to modern collectibles?

The samurai katana's evolution from historical military and ceremonial objects to modern collectibles spans roughly 150 years, from the Meiji period prohibition on sword wearing in 1876 to the present day. The prohibition did not end sword production - it redirected it. Japanese swordsmiths who had produced swords for samurai patrons shifted to producing swords for collectors, cultural preservation, and later, for art sword competitions that maintained the traditional production standards. The tamahagane steel smelting process, clay tempering, and hand polishing all continued in Japan through the modern period as craft traditions rather than military production. Outside Japan, the post-World War II period saw growing international interest in Japanese swords, which created demand for well-made replicas using traditional construction methods. Modern collectible samurai katana are the result of this evolution: they use the same production methods as historical swords - high-carbon steel forging, differential clay tempering, hand fitting - but are made as display and collecting objects rather than functional swords for martial use. The quality range is wide, from entry-level production pieces to hand-crafted swords that approach historical production standards.

What is the correct way to hold and handle a samurai katana?

Handling a samurai katana correctly protects both the sword and the handler. The first rule is to always be aware of where the cutting edge is - the edge faces upward when the sword is in its saya in the display position, and it faces toward the target when in the hand. When picking up a katana from a display stand, grasp the tsuka with the dominant hand in a full grip rather than a partial or pinching grip, keeping fingers away from the blade at all times. When drawing the sword from its saya, the left hand holds the saya stable while the right hand draws the blade - a controlled motion that keeps the edge moving away from the body. When examining the blade, hold it with the edge facing away from you, handle toward you, and tilt the blade at a shallow angle under a light source to reveal the surface character of the steel and the hamon. After examination, wipe the blade gently with a soft cloth from the habaki toward the tip to remove fingerprint oils before returning it to the saya. Never touch the blade surface directly with bare fingers - the oils in skin cause spotting and long-term oxidation on carbon steel.